(Yes, AI wrote my headline.)

In this post, I’ll outline how we’re using artificial intelligence (AI) to help us develop online learning and I’ll share four key pieces of advice based on what we’ve learned this year.

We’ve been using generative AI which is a type of AI that can generate text, images, media, ideas and more. You can type in instructions and questions and interact with the AI in a natural, conversational way, a bit like a chatbot. Some well known examples are OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Bard.

Our first steps with AI

Since the explosion of easy to use generative AI-based tools at the beginning of this year, a lot of the focus in educational circles has been on students’ use of AI, the potential for cheating and what this means for academic integrity. But, as a learning designer working with time-poor academics to develop modules to tight deadlines, my interest has always been in how we can use AI as a tool for creativity and productivity.

Before I launch into this, though, a disclaimer: AI applications like ChatGPT are merely a tool, and you should treat everything it outputs with plenty of scepticism. Our policy is that we would never publish anything generated by AI without approval from the academic subject experts we are working with. More about this, later.

Why bother with AI?

We’ve always asked a lot from our academic colleagues when designing online modules: not only do we ask them to design the teaching and learning activities for an entire module, as well as all of its materials upfront, but they also need to learn what works best in an online, asynchronous environment, with students from all over the world, and get to grips with technologies they may never have used before. As well as being experts in their field, we want them to be creative enough to come up with rigorous activities for students to apply their learning, we want them to be charismatic presenters at ease in front of a camera, and we want them to do all of this on top of their on-campus commitments. One of the benefits of AI, I think, is to give more opportunities for learning designers to really think about activity development, using AI to help with this, turning the academic role into more of a curator of activities and resources than a creator of original content – hopefully freeing up time for them!

As a department, we have spent the last few months testing out AI applications and tools to explore their capabilities for module development. We’ve been experimenting with different prompts for ChatGPT in an effort to be able to get the best from it, and we’ve also been researching and trying out many other AI educational tools, which have emerged in large numbers over the last few months. A few examples of the tools we’ve explored include:

- ChatGPT and Bard for generating ideas for content and learning activities

- H5P Smart Import to quickly create interactive online learning content

- Education Copilot to develop lesson plans

- Tome for generating attractive clearly designed lecture slides

- Albus for organising and suggesting new ideas.

This isn’t a full list and we aren’t using these tools regularly, yet, but it’s been fascinating to see what AI can do!

Four tips for getting started

If you are looking to do something similar and you don’t know where to start, here are four tips for how to go about it.

1. Ask what problems you need to solve

Rather than thinking about what AI can do for you (which is a lot, and can be overwhelming), start by identifying the problem you need to solve.

| Area | How could we use AI |

|---|---|

| Learning design | Activity ideas |

| Writing formative MCQs | |

| Narrative (e.g. introduction, conclusion) | |

| YouTube synopsis | |

| Production | Creating slides using lecture scripts |

| Video | To correct mistakes |

For example, we wanted help with writing formative multiple choice questions (MCQs). This is a time-consuming, effortful and quite boring task – but it’s not necessarily something that needs to be done by an academic subject expert, especially when the questions are based on a particular reading or video lecture. So, we looked at ways that we could get AI to automatically create MCQs from the content we already had.

We experimented with using ChatGPT to create MCQs based on lecture video transcripts or readings written by our academics.

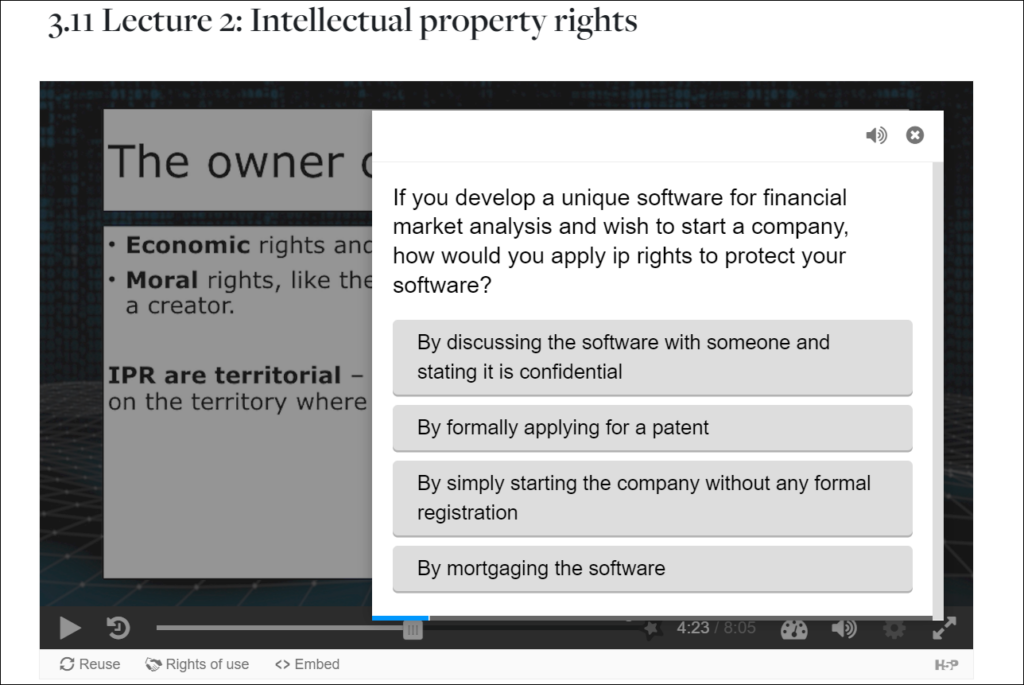

We’re currently trialling a paid service from H5P Smart Import, which can create in-video questions for our videos along with MCQs, glossaries and longer-form questions based on our readings and transcripts.

We’ve shared some of this experimental output with our academic colleagues and have received positive feedback. We’ve found that they still need to curate the questions (deleting ones they don’t think are relevant; making sure the correct answers are actually correct), but it can save them so much time.

By identifying problems like this, it gives a focus or purpose to the research and trialling you have to do with different tools and software. It then also gives you an easy way to win over AI-sceptics in your organisation, as you’re fixing a problem they probably want solved, as well!

2. Consider whether AI really adds value

There are AI tools out there that will do basically anything you can think of – but just because they can, it doesn’t mean that you should use them. As an extension of identifying your problems, when you find a solution, really consider whether it adds the value that you want it to.

For example, the process of filming lecture videos is one of the most costly parts of online module development – it involves a lot of time and collaboration between many different colleagues (academics, academic editors, video editors, motion graphic designers, media developers). So, we explored some of the AI options for video development. A popular example is something like Synthesia, which allows you to generate videos with AI avatars who can voice your script. Personally, however, we didn’t feel like this was adding the value we were looking for.

One big reason we create videos presented by our academics is that it adds a face to the module and can create a sense of connection for the students when the same person presents the videos all of the way through – and this is really important for students who are studying online, asynchronously and do not have the same opportunity to connect with others as on-campus students. AI avatars may reduce some time or financial burden on creating lecture videos, but they aren’t able (in our opinion) to create the same connection.

3. Be sceptical of AI output, and educate colleagues

Generative AI is not infallible; it has its drawbacks just like any other piece of technology. It can be wrong, it can be biased, it can hallucinate things, it can ignore or forget pieces of the instructions that you give it and it can be superficial. Just because the output looks correct, it doesn’t make it so. This is why we have decided that we would never publish content that we’ve generated with an AI tool without having a subject expert approve it, and this is why we are developing guidance for colleagues using AI to help them get the best out of it.

It’s really important that if you want to use generative AI for course development, that you take a step back and think about the impact of it, the potential consequences, and how you are going to manage it.

4. Always make sure you are designing with students’ best interests in mind!

As with anything related to learning design, you should make sure that you are using AI tools with students’ best interests in mind. This relates partly to the point I made about value, above. At the end of the day, any tools or technologies we want to use are there to help us provide a better learning experience for students – there’s no point using a tool that saves time if the output is worse for students. We always want to make sure we are putting students’ best interests at the forefront of everything that we do.

We hope you found this post useful! Keep an eye out for our posts in the future, where we’ll talk a bit more about the AI tools we’ve been experimenting with, and some guidance for writing prompts to get the best results.